Thirty years after their invention, employer value propositions (EVPs) have gone from “a new way of thinking about how we attract and hire talent” to “the generic platitudes we send to make us look good.”

In the process, we’ve gone from employer branding to employer blanding.

The main driver of platitude-driven EVPs is a disconnect between the audience an EVP is intended to influence, and the audience who pays the bill.

EVPs are meant to make it clear what a candidate will get when they join and, in a best-case scenario, why someone should choose this company over all others. They distill the reasons why people join and continue to stay at this company, which means they are best when they connect to what the candidate wants to know about a company.

Proven Systems for Business Owners, Marketers, and Agencies

→ Our mini-course helps you audit and refine an existing brand in 15 days, just 15 minutes a day.

→ The Ultimate Brand Building System is your step-by-step blueprint to building and scaling powerful brands from scratch.

Table of Contents

Current Trends in Employer Value Propositions

Let’s take a recent article from Built In listing 24 EVPs to Inspire. These are supposed to be great examples of employer value propositions. But what do we find?

Claims better focused on potential customers. For example:

- “We strive to be the very best at what we do”

- We have a smart, ambitious team dedicated to delighting our customers”

- “We’re an industry pioneer that’s been leading the way for over a decade”

Things are probably true at almost every company. For example,

- “We love what we do and strive to do the best work we can each day”

- “When smart people work on intriguing problems, and they enjoy coming to work each day, they accomplish great things together”

- “We’re looking for friendly, creative problem solvers to join our team”

Demands rather than offerings. Examples include:

- “We are looking for people who are passionate, curious, and collaborative”

- You will engage in interesting and challenging work that will improve the lives of our athletes”

- “Employees who are creative, energetic, proactive, and intelligent in both their thoughts and actions”

And things that are simply impossible to prove. These include:

- “We believe our winning culture sets us apart”

- “We have a phenomenal culture and unparalleled drive”

- “Our team is high-powered and committed”

Common Pitfalls in Employer Value Proposition

While I am certainly cherry-picking, there’s nothing here that shapes candidate expectations in concrete or credible terms, or explains why they should choose this company over the other 23 on just this list, let alone the tens of thousands of other companies looking for similar hires.

Misalignment Between EVP Creators and Target Audience

The root cause is a disconnect between the people the information is intended for (applicants and candidates) and the people who are responsible for creating and funding it (leadership).

Executives are not motivated to provide a transparent and credible view of the company. Instead, they treat EVPs as opportunities to say nice things about the companies they lead. As you can see in the above examples, they are equally focused on using EVPs to communicate with consumers as they are with candidates, diluting their value.

The Problem with Overly Positive EVPs

Presenting the rosiest possible picture may appeal to the C-Suite, but it doesn’t inform the candidate. Upon being fed a steady diet of generic platitudes and aspirational spin, candidates with options will gravitate to a place that reveals a more complete picture of working there. And that means the good and the bad.

More Applicants Isn’t Always Better

Because they only show the positives, these EVPs are effectively designed to attract the maximum amount of interest.

Employer branding is possibly the only aspect of marketing where getting more leads is actually detrimental to success. Where consumer and corporate marketing want the maximum number of leads to sell to, employer branding wants fewer applicants of higher quality.

While every dollar is a good dollar in sales, every applicant is not a suitable applicant. It is the only place where quality trumps quantity.

Focusing on the Wrong Metrics

Finally, most EVPs are following the wrong north star: letting performance marketing metrics dictate rather than branding metrics.

Consumer marketing also often suffers from the same issue. Trying to measure the brand’s value by looking at the number of clicks and impressions it gets, is trying to measure a fish by how well it climbs trees. When you track performance metrics, you end up reinforcing the worst behaviors of EVP development and end up creating something that nobody would object to.

All in all, it means that EVPs aren’t serving companies because they aren’t serving the candidates.

A Proposed Model For Getting To The Heart of What Candidates Want

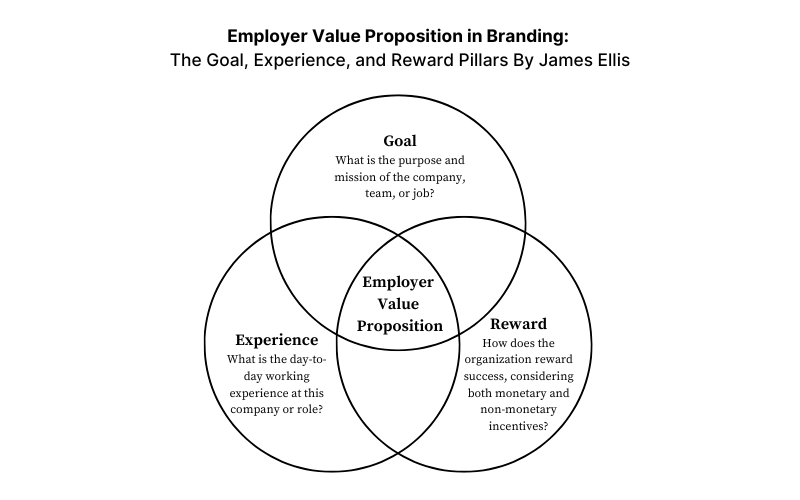

Standing in a candidate’s shoes, we can design a framework that tests to determine if an EVP is creating useful differentiation.

There is abundant evidence about how candidates make choices in their next role. We know what they want to know about their next employer, team, and job.

Goal: What is the mission of this company, team, or job? This is directional in nature and can be massive (“goes to Mars” for SpaceX, “organizes the world’s information” with Google, or “saves the planet” with the Environmental Defense Fund) or more modest (help families get house loans, ensure that trains in a given area run safely, or tell stories about customers). For people who are driven by the satisfaction of working as part of a team to achieve something more than they could on their own, this is what they want to understand.

Experience: What is the day-to-day working experience at this company or role? Is it collaborative or competitive? Autonomous or directed? A culture of experimentation or optimization? Rote process or perpetual invention and discovery? Room for disagreement, or value placed on consensus and dogma? Every company behaves differently, so what is the experience at work, and will it align with how I like to work?

Reward: How do we reward success? This can be as obvious as the salary and the bonus structure (and on what basis will the bonuses be allocated), but it goes deeper. Will I receive a boost in status for working here? Will I get a title that will make it easier to get an even higher-paying job somewhere else next year? Many people are driven by that feeling of achievement and the rewards that come with it, ignoring any challenges and obstacles in the process.

Put another way, what candidates want to know is: What are we trying to accomplish, how will we do it, and what will I get when we do?

Achieving Differentiation in EVPs

Through this lens, most EVPs and related pillars look like expensive bumper stickers. Ideas like “igniting your potential,” “driven by you,” and “be the catalyst” sound empowering and attractive but don’t actually say anything. How will a company ignite my potential? By sending me to class? By mentoring me? By putting me in the room with their best clients? Or by giving me the thorniest problems to tackle? Or showering me with praise? Will they ignite my potential by offering an above-average salary or letting me work from anywhere?

The issue is that most people would love to have their potential ignited in some form. They would love to drive things or be a catalyst. Those ideas are probably attractive whether they worked for Pepsi or Goldman Sachs.

This is why they aren’t useful as EVPs. It’s like a restaurant with a sign that says, “We have good food!” Doesn’t every restaurant think it serves good food? Is anyone ever in the mood for bad food?

A modern EVPs aim to express the company in a way that maximizes the number of people who will find it attractive, but it does so by finding things that few people can object to.

Compare that to the Goal/Experience/Reward model. It becomes obvious to a candidate that what the company offers is different and genuinely appealing. A candidate might be driven by the goal enough to forgive a less-than-optimal work experience. Or they might be willing to hold their nose and drive an outcome they aren’t thrilled by if it means clear rewards.

One of the challenges in the EVP space is the complaint that not all businesses can be unique. But this model makes it clear that a business doesn’t have to be unique in every regard, so long as it picks its point of differentiation.

The knock-on effect of this model is that it democratizes employer branding. More companies can develop and use their brand to attract great people because they are grounded in common ideas about what candidates want rather than a dance around what will avoid turning some candidates off (who, by the way, are candidates they wouldn’t want to hire anyway).

This is moneyball employer branding: rejecting the usual expectations of what an EVP is supposed to look and feel like and building on the ideas that drive results.

For companies ready to think of their EVP as a tool to create choice amongst their target talent instead of painting to cover cracks in the foundation, building a brand with a candidate-first approach will actually help hire better talent faster.